This post is the first in a series of ‘meet the expert’ articles about the investigators working at the MRC-University of Glasgow Centre for Virus Research. These posts are written by the CVR students and researchers and are designed to educate, engage with and inform the public and fellow scientists about who we are and what are our motivations. Veronica Rezelj (PhD student in the Elliott lab) interviews John McLauchlan, PhD, the associate director of the CVR who focuses on investigating the hepatitis C virus (HCV). John is the co-chair of HCV Research UK, a consortium of clinicians, scientists and epidemiologists, a director of its HCV Research UK ‘Biobank’ and a partner in the MRC Stop HCV consortium.

How and when did you become interested in HCV? What made you want to do research in HCV?

I became interested in HCV almost 2 decades ago. The virus had only been discovered in 1989 and it was becoming increasingly clear that this was a medically important problem across the globe. One of the challenges faced by clinicians was that the available drugs worked poorly to treat anyone infected.

For scientists like me, there were very few tools to study the virus and in fact no models in the laboratory to grow HCV. So it was very much a case of building projects that still allowed us to examine the various components of the virus but not in a way that virologists would normally use. There was a lot of head scratching to try to overcome problems. Some of them still exist today even though there are now fantastic drugs that are much more effective at curing infection.

What are your research interests?

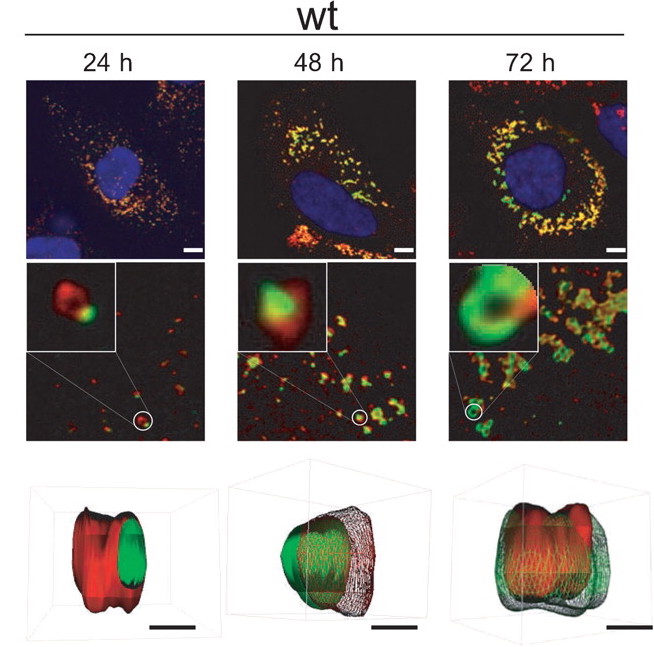

Broadly, my main research interests focus on virus-host interactions during HCV infection. For a long time now, we have focused on identifying host factors and organelles [lipid droplets for example] which allow the virus to replicate its genome and then release infectious virus particles from cells. These studies relied on cell-based systems which had been developed to investigate the whole of the virus life cycle. In recent years, my focus has moved more towards how we can apply these systems using the knowledge we obtain from looking at natural infection. This has meant becoming more involved in clinical studies, which I find fascinating and led to the creation of HCV Research UK.

We are now starting to benefit from those clinical studies. For example, strains of HCV can be assigned into up to 7 different viral genotypes based on their nucleotide sequence. The most prevalent strains in the UK are genotypes 1 and 3. It is known that response to therapy and development of liver disease are not the same for these two genotypes. We have been looking at liver samples from patients infected with either genotype 1 or genotype 3, and the host genes which are altered in expression are not the same. So the host response to infection is dependent on the infecting viral genotype and this may help to explain the different outcomes for therapy and liver disease.

We are building on such findings to try to understand at the molecular level why these two genotypes give different responses and this may help to predict in the infected population who responds to treatment and may develop liver disease.

You are leading a project funded by the Medical Research Foundation to establish a clinical database of HCV patients. 10,000 patients were recruited ahead of the target date. What, in your opinion, was key for such an impressive recruitment success?

The consortium we set up, called HCV Research UK, to recruit all of these patients has been an arduous task for a whole group of people and there are many factors in its success. First and foremost, the patients who are infected with the virus have been incredibly willing to consent to provide data and samples for the cohort. Even with the best organization, we would have had nothing without their cooperation.

Secondly, we put a lot of effort into bringing together clinical centres from across the UK and have been as inclusive as possible. What we found was that as we gathered momentum, more centres wanted to join and this undoubtedly helped us to reach our target more quickly than expected. Ultimately, we have now created a network of 60 sites across the UK, which is a major feat in itself.

Thirdly, we set up a well-organised centralized infrastructure for collecting data and samples. This means there is a common set of standards and datasets for HCV Research UK, which is really vital for large scale clinical studies.

How do you think this cohort study will aid clinical HCV research?

We are already seeing the benefits of setting up HCV Research UK. There has been funding from MRC to establish STOP-HCV, another consortium that will use primarily samples from the HCV Research UK biorepository. STOP-HCV will aim to identify viral and host genetic signatures that predict who may respond better to therapy and also who may or may not develop liver cirrhosis.

HCV Research UK is also collecting data and samples from patients receiving new drugs that cure HCV infection as part of an Early Access Programme. About 1000 patients who could die from liver disease in the next year unless they are given these drugs are in the programme and the majority of them have been recruited into HCV Research UK.

“Having a cheap, readily available vaccine to prevent HCV infection would be a holy grail for the entire field”

This type of real world study is absolutely essential to understand how the drugs will perform outside of clinical trials. The data and samples are already being analysed so we can answer some essential questions about how efficient these new drugs are and which patients may benefit the most from receiving them.

What are or will be the latest significant advances in HCV research? How close or how far away are we from a Hepatitis C vaccine?

Having a cheap, readily available vaccine to prevent HCV infection would be a holy grail for the entire field. How far away we are from having a vaccine is difficult to judge but there are many groups, including those at the CVR, who are actively looking at new approaches.

To some extent, it is similar to a vaccine against HIV; there have been promising candidates but all have failed and so we have to rely on antiviral drugs. The difference with HCV compared to HIV infection is that the drugs do clear the virus while for HIV, they will only suppress infection. So if you had to ask me what has been the latest significant advance in HCV research, it has been the development of a range of new antivirals which are able to clear infection with a high success rate.

What potential problems do you foresee for the above mentioned advances?

Staying on the topic of antivirals, the potential problem could be the development of resistant strains. History has told us that viruses usually have a sting in their tail when we think they are beaten. HCV is a highly variable virus and so it will be important to monitor new infections for possible emergence of resistance. There are about 130-170 million [people] around the world who are infected. That represents a very large reservoir of infection, enough for the virus to potentially adapt to antivirals.

What is your everyday life like? What do you enjoy doing in your free time?

Well, work keeps me busy. As well as running a research programme and heading HCV Research UK, I also have some responsibilities for the day to day running of the CVR. I do enjoy the challenges of my job even with all of its ups and downs. The best part is always when someone has exciting data.

For my free time, I enjoy spending time with my family, especially my two grandchildren Betsy and Henry. I also like doing some DIY around the house although it’s never as good or as quick as a professional. Finally, I do enjoy football and have to admit to being a Partick Thistle supporter. They are frustrating to watch but, just as in science, unpredictable good results do happen from time to time!

By Veronica Rezelj Ph.D student

The MRC-University of Glasgow Centre for Virus Research undertakes a broad research programme into HCV biology ranging from epidemiological and clinical to molecular and cell biological studies. This research is led by the principal investigators: Dr Carol Leitch (HCV evolution); Dr John McLauchlan, associate director of the MRC-University of Glasgow Centre for Virus Research (HCV cell biology and immune responses, as well as being a leader of the ‘HCV Research UK’ ‘Biobank’); Dr Arvind Patel (HCV entry and vaccine development) and Dr Emma Thomson (HCV evolution and treatment in the clinic).

Thanks to fellow CVR blog contributors for critical reading of this post.

[…] post is the second in a series of ‘meet the expert’ articles about the investigators working at the MRC-University of Glasgow Centre for Virus […]